Intersectionality and Critical Race Theory

Key Terms:

- Intersectionality: the idea that social identity categories such as race, gender, sexuality, class, dis/ability, religion, and age compound and reinforce each other through interlocking forms of oppression.

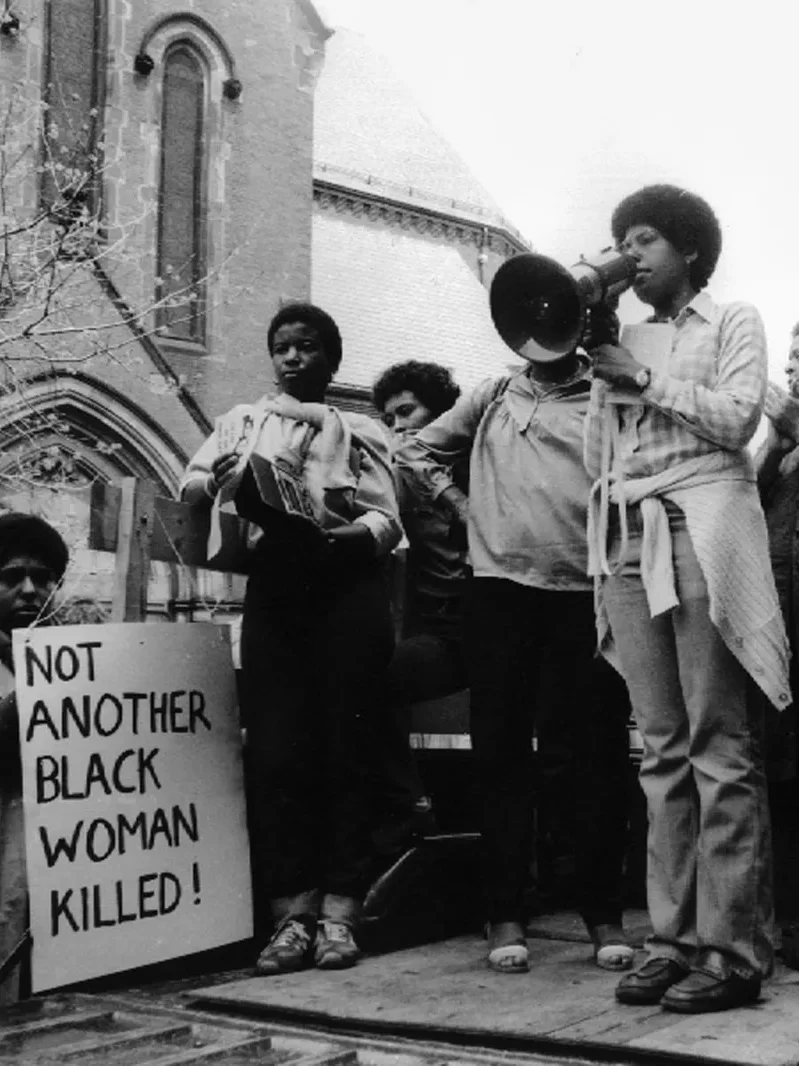

- Popularly coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991) to articulate Black women’s experiences of both racism and misogyny.

- Matrix of domination: the network of intersecting forms of oppression; we can locate ourselves on the matrix of domination by considering all of our social identities and their positioning in social hierarchies (Collins, 2002).

- Critical Race Theory (CRT): a framework that “brings attention directly to the effects of racism and challenges the hegemonic practices of White supremacy as masked by a carefully (re)produced system of meritocracy” (Brown-Jeffy & Cooper, 2011, p. 70).

“[W]e find our origins in the historical reality of Afro- American women’s continuous life-and-death struggle for survival and liberation. Black women’s extremely negative relationship to the American political system (a system of white male rule) has always been determined by our membership in two oppressed racial and sexual castes.”

– Combahee River Collective (1986)

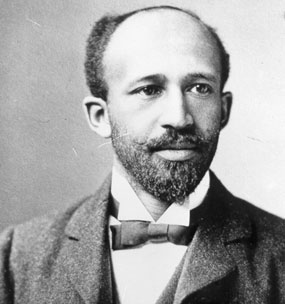

“It must be remembered that the white group of laborers, while they received a low wage, were compensated in part by a sort of public and psychological wage. They were given public deference and titles of courtesy because they were white. They were admitted freely with all classes of white people to public functions, public parks, and the best schools. The police were drawn from their ranks, and the courts, dependent on their votes, treated them with such leniency as to encourage lawlessness.”

– W.E.B. DuBois (1935, p. 700-701)

As these revolutionary Black activists suggest, white supremacy systematically upholds and is upheld by all other forms of oppression and discrimination. In order to combat these interlocking forms of oppression, it is critical that our movements for liberation are also deeply intertwined. Although this website is primarily focused on racism and the effects of white supremacy, I adopt the lens of intersectionality to show how this work is informed by interdisciplinary activism and in service to multiple forms oppression.

It is also important to acknowledge that these categories of identity such as race, gender, and sexuality are socially constructed: they are labels for classifying human difference that have been used to rationalize unequal distributions of power and resources throughout history (Adams et al., 2023; Willey, 2017). In order to denaturalize racialized oppression, it is critical that we recognize the hierarchical power that racial categories hold in our society while also problematizing their biological funding.

As a resource for anti-racism, this website also contributes to necessary conversations about critical race theory (CRT) in music education. Although it has been demonized in media outlets and debates about education (Ray & Gibbons, 2021), CRT is a valuable scholarly tool for analyzing the ways in which racism and white supremacy impact and shape our society. In recent years, music education scholars have begun to apply CRT to music teaching and learning practices in order to bring race to the forefront of common pedagogical considerations such as culturally relevant teaching (Ladson-Billings, 1995), critical literacy (Beach & Bolden, 2018), popular music education (Powell et al., 2019), and social justice education (Spruce et al., 2015). Some emergent themes in the literature on CRT in music education include the importance of using explicit and direct language in anti-racist discourse (Bradley, 2007; Hess, 2017b), considering student and teacher positionalities (Clauhs, 2021; Hess, 2017a) and countering dominant deficit narratives (Clauhs, 2021; Hess, 2018). This website aims to extend the work of these scholars through practical methods for incorporating critical race theory in music education.

Emergent Strategy and Transformative Justice

Key Terms:

- Emergence: “the way complex systems and patterns arise out of a multiplicity of relatively simple interactions” (Obolensky, 2010, p. 88)

- Emergent strategy: a framework for community-based change; “how we intentionally change in ways that grow our capacity to embody the just and liberated worlds we long for” (brown, 2017, p. 5)

- Interdependence: a central element of emergent strategy; urges us to “attend to the relationships and power dynamics in the rooms [we] hold, creating structures that support authentic, intimate relationships, mutual transformation, and collaboration” (brown, 2021, p. 9)

- Restorative justice: addresses conflict by emphasizing collaborative peacemaking and healing for the offender, the victim, and the community; an alternative to the punitive, retributive justice practices and systems (Nocella, 2011)

- Transformative justice: builds on restorative justice by examining how conflict and harm are rooted in systems of power and oppression (Nocella, 2011)

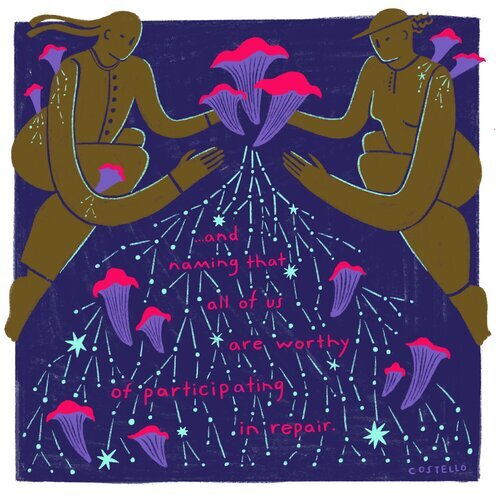

“I believe that transformative justice is actually a crucial element in moving toward the kind of large-scale societal healing we need— transformative justice is a way we can begin to believe that the harm that has come to us won’t keep happening, that we can uproot it, and that we can seed some new ways of being with each other”

– adrienne maree brown (2019, p.8)

Like many of the institutions of our society, schools often rely on punitive disciplinary systems and top-down authority structures. This leaves many students and teachers—especially teachers of historically undervalued subjects like music—feeling small and powerless as those in positions of power rarely hold the values, priorities, intuition, or care that drives meaningful, lasting change. Instead, emergent strategy provides a path to transformation that is built on the emotional labor and care work that is integral to teaching jobs. Although we may feel small in comparison to the massive issues we are facing, we are made stronger through our interdependence and through a multitude of small acts. I share the framework of emergent strategy with music educators to empower us all to transform the world by changing ourselves and investing in our relationships and communities.

Although they are certainly helpful frameworks for teachers, restorative and transformative justice also have positive outcomes for our students. Some scholars have begun to explore the implications of restorative and transformative justice in music teaching and learning. For example, O’Neill (2015) proposes transformative music engagement as a process that emphasizes critical reflection, process over product, inclusivity, experiential learning, and differentiated instruction. This educational approach seeks to “enable and encourage youth empowerment in music learning in ways that strengthen youth voices, wellbeing, and musical flourishing” (p. 389). Additionally, Cohen and Duncan’s (2015) work on restorative music-making with incarcerated populations shows how music can be used for processing and healing from conflict. They use this work to suggest transformative approaches to music education pedagogy, learning activities, and classroom management that consider students’ needs, lived experiences, backgrounds, and traumas. The work of these music education researchers further demonstrates the degree to which large-scale transformation can occur through relatively small changes in our learning spaces and communities.

Ultimately, this website frames transformative justice as a central goal. Through engagement with the content, music educators will have the ability to analyze the ways that our teaching practices or behaviors may be rooted in racism. Rather than simply treating or masking the symptoms of white supremacy, we will critically consider how we can actively and fundamentally orient towards anti-racism in ourselves and our relationships with others. If we commit to this life-long endeavor, the effects will extend far beyond our classrooms and learning spaces.

Activist Music Education

Key Terms:

- Activist music education: a pedagogy oriented toward social change that aims to provide youth with the tools for connecting with others across differences, honoring and sharing lived experience, and developing the ability to think critically about the world around them (Hess, 2019)

- Conscientization: the “process through which people become aware and reflect upon the conditions that shape their lives” (Hess, 2019, p. 19); the development of a critical consciousness (Freire, 2000)

- Praxis: the “interrelated processes of reflection and action toward transformation” (Hess, 2019, p. 15)

- Abolitionist teaching: “the practice of working in solidarity with communities of color while drawing on the imagination, creativity, refusal, (re)membering, visionary thinking, healing, rebellious spirit, boldness, determination, and subversiveness of abolitionists to eradicate injustice in and outside of schools” (Love, 2019, p. 2)

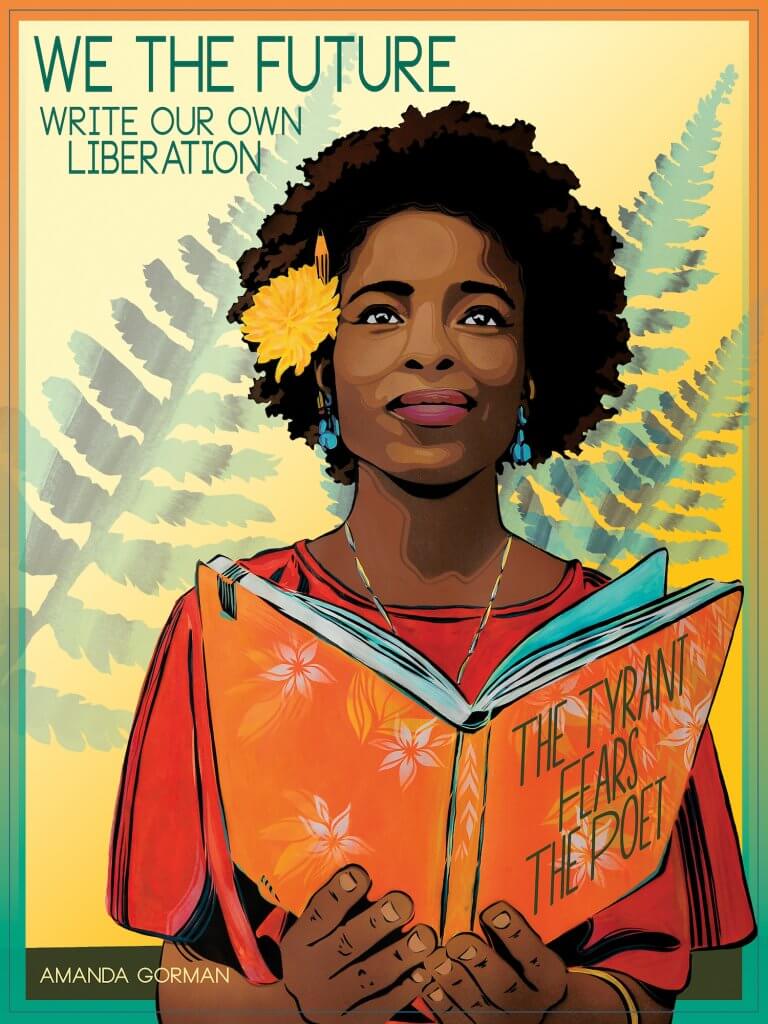

“To resist oppressive ideologies circulating nationally and globally requires more than just an active stance that encourages youth to think deeply about what they encounter in the world and to trust their own experiences and voices; such resistance also requires broader mechanisms for expression, communication, and knowing. Music education innately provides such opportunities.”

– Juliet Hess (2019, p. 6)

Hess’ (2019) conceptualization of an activist music education pushes the field towards direct collective action. Under this pedagogy, students develop their abilities to think critically about the world around them, participate diverse community-building, and value lived experience. By pushing toward these goals, music teachers can work with their students to create anti-oppressive futures. Further, drawing on the work of several music education philosophers, Hess asserts that music is a particularly useful vehicle for social change because the activist functions of communication, identity exploration, expression, and reinforcing or challenging personal values are inherent in relational music-making. In developing an actively anti-racist music education, Hess’ music education for social change provides strong foundations for the teaching practices contained in this website.

Another revolutionary educational philosophy is Love’s (2019) abolitionist teaching. Love addresses several gaps in mainstream education systems that limit the potential of students of color including the imposition of deficit narratives, the maintenance of socio-economic stratification, and the minimal progress offered by school reforms. Instead, Love proposes abolitionist teaching as a radical alternative to the unchanging educational systems fueled by white supremacy and capitalist greed. Although this website is more focused on practical applications rather than systemic change, the anti-racist music education we are working towards is aligned with Love’s visions for abolitionist teaching. Both Hess (2019) and Love (2019) allow us to envision the role that music might play in educational institutions that are fundamentally aimed towards eradicating injustice, participating in active resistance, and centering student joy.